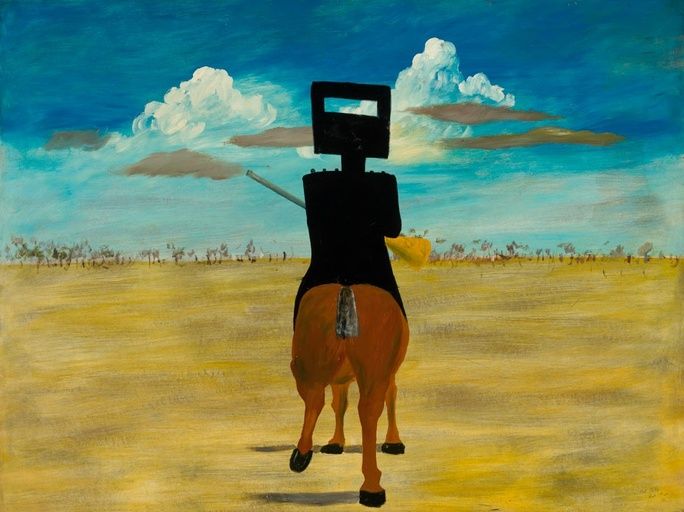

Ned Kelly, 1946

Sidney Nolan Ned Kelly, 1946 National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Gift of Sunday Reed, 1977

Shaun Gladwell is an Australian contemporary artist whose work spans moving image, painting, photography, sculpture, installation, performance and virtual reality.

"Kelly is riding alone, across an open plain. The sharp sunlight delineates all the forms before us - the horse, Kelly’s gun, the distant tree line on this yellow sandy expanse. Everything is clearly and quickly articulated except for that famous body armour and helmet, which magically absorbs all light. Indeed, it is as if light particles are ‘bailed up’ and robbed by the event horizon of this formal black hole. Kelly’s helmet and armour become unknown volumes: both flat and a window into infinite space. Apollo’s order and sunlight is no match for a Dionysian Kelly, who in this instance may be simply riding, but if needed, he will dismount, disarm, endure 20 rounds of bare knuckle boxing and win.

This painting of Kelly is arguably the most well known of all Nolan’s works, and certainly the most recognisable of his initial Kelly series. Nolan depicts Kelly riding freely and, more importantly, for his own sense of freedom. We are given a vision of Kelly, the firebrand anti-establishmentarian, in a very precious moment. We are alone with him, away from the gang and all the transpiring drama. From this moment of solitude, we envisage our outlaw riding into his destiny.

Nolan’s image is a technical mirroring of its subject matter. It is also painted ‘freely’, in the spirit of our great anti-hero, Kelly. Nolan's technique dances above and around the strict academic laws of volumetric illusion, typically achieved through tonal modelling, accurate proportion and perspective. Nolan instead plays the game of figurative representation in his own idiosyncratic way, subverting artistic convention in the creation of a very ‘modern’ composition.

The image has such a graphic intensity that it burns into one’s retina, and even deeper into the individual unconscious. Soon enough, this image of Kelly gallops directly into the collective imaginary of an entire nation and the primers of art history. The 1946 Kelly will effect a shift from being one of many representations of Kelly to possibly the most recognised artistic symbol of this man. Even in terms of other dramatisations of Kelly, can the film interpretations of Mick Jagger or the late, great Heath Ledger, or Julian Schnabel’s ‘plate painting’ of Kelly, ever come close to claiming the iconic power of Nolan’s 1946 Kelly?

A great mystery of the painting is the much speculated upon visor in Kelly’s helmet. To see directly through the helmet form (which we know from Nolan’s statements, was inspired by Malevich’s black square) is to enter a wonderful representational dilemma. Is Kelly hollow, or a ‘body without Organs’ as the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze would put it? Is ‘Ned’ constructed purely of mythic surfaces? Nolan would later famously state that every painting of Kelly was in fact a self-portrait. The transparent visor in the helmet suggests that we can all inhabit this empty armour and ask ourselves: do we have it within us to be so wild, so passionate, so revolutionary?

The see-through helmet also destabilises the otherwise clearly defined figure/ground relationship. Kelly is stark against the immediate surroundings, but this vivid nature is also within him. Kelly’s agency is extended into the sky through this very powerful pictorial device. To be simultaneously solid and transparent – a dark Dionysus framing Apollo’s light. Given Nolan’s great interest in poetry, I cannot go past images conjured in T.S. Elliott’s ‘the Hollow Men’ (1925). While this poem might not be comparable in thematic, as far as imagery goes the poet’s utterances of “shape without form, shade without colour…”, “The eyes are not here, There are no eyes here…”, “Behaving as the wind behaves” and of course, the poems title, are all evocative of Nolan’s eventual 1946 Ned Kelly portrayal.

We simultaneously look at Kelly and look through him, but from behind, as with Casper David Frederich’s Wander Above the Sea of Fog (1818) (this time on a plain rather than a peak). As with Frederich’s figure, we assume we are seeing what Kelly is seeing before him – a vast open expanse. However, instead of us simply looking at Kelly who in turn ‘looks out’, Kelly is looking back at us through the sky itself. He is there before us and already away, taking Nolan with him, into the afternoon, then evening, and into a posterity of open sky and brilliant stars."