Sidney Nolan: Colour of the Sky - Auschwitz Paintings

This exhibition by the Sidney Nolan Trust is a double world first. It is the first time Sidney's long-hidden Auschwitz works have been publicly exhibited, and the first time their dramatic story has been told in its entirety. After nine years’ researching and writing, Andrew Turley agreed to mark the occasion by revealing the full history of their making, providing it to accompany the 32 paintings and photographs on display at The Rodd (August - October 2021).

The following is a full and complete extract from his forthcoming book Nolan's Africa.

Nolan's Africa is now published by The Megunyah Press.

Nolan's Auschwitz

In January 1962 Sidney visited Auschwitz, and although his association with concentration camps stretched back decades it shook him to his core.

As early as 1939, while living in Melbourne, Sidney had begun to paint their darkness. (1) In 1944 he completed 'Lublin', the same year the Russian army pushed west toward the heart of Germany, reclaiming the Polish city en route. Before the war, Lublin had been an important centre of Jewish culture. By the end of it, Lublin's Jewish population had been almost entirely eradicated after the Nazis established a ghetto within the city limits to house Jewish and Polish families forcibly relocated after confiscation of their property. Overcrowding, disease and lack of health services were ghetto norms. A deliberate Nazi policy of starvation sapped their strength and many starved to death as they waited to be shot in the forest or packed shoulder to shoulder in the gas chambers of Maidanek, Sobibor or Belzec. (2)

Sidney's 'Lublin' featured two building facades pierced by square windows. Each window trapped a single distraught face below or beside a row of chimneys, stark reminders of the crematoria that ringed the city. When he and wife Cynthia gifted it to the Art Gallery of South Australia in 1974 Sidney added a second title - 'Baroque Exterior' - the name of an Ern Malley poem whose first lines read:

When the hysterical vision strikes

The facade of an era

It manifests its insidious relations.

The windowed eyes gleam with terror

Sidney's close friend George Ivan Smith recalled, "He deplored human suffering because people were outside the magic circle or influence.” (3)

In June 1955 Sidney cut and kept several disturbing newspaper articles with his diaries. (4) One titled "Alleged 'Bargain' with Nazis over Hungarian Jews" detailed the collaboration and corruption that "filled train after train" with Jews, sending 500,000 of them "through the countryside most of them knew well, and expected to see again, to death at Auschwitz". Two years later, on his way to the Greek Island of Hydra and the beginnings of his infatuation with Gallipoli, Sidney made himself a note. "Do European Scene of Camps on scale of Lascaux" he wrote (5), drawing parallels between prehistoric paintings of extinct animals in the famous French cave system and the human extinctions of Poland and Germany.

It was four years after that, and almost twenty years after 'Lublin', that Sidney came face-to-face with the Nazi extermination camps and some of the worst human suffering the world had ever seen.

The experience was triggered by the capture of Adolf Eichmann. During World War II Eichmann had been the head of the Reich Security Main Office Section IV B4, which concerned itself with "Political Churches, Sects and Jews". Appointed head of the emigration office in Vienna he had driven Austrian Jews from the country and taken the minutes of the 1942 Wannsee Conference, consolidating plans for the eradication of Jewish people in Europe. (6) He went on to mastermind the ruthlessly efficient railway system feeding the death camps and was famously quoted as saying "I'll set the mills of Auschwitz grinding". (7)

The effectiveness of Eichmann's transport system had been chilling. Trains with cattle cars were commissioned with one-way third class travel services to concentration camps billed to the SS. Group rebates applied and infants under four were transported to the gas chambers at no cost. The SS paid fares with assets stolen from the Jewish population and the business of death was integrated into regular railway schedules. As a result Auschwitz-Birkenau became the site of the largest mass murder in world history. (8)

Eichmann disappeared after the war, but Nazi Hunters tracked him to Argentina and on 11th May 1960 Mossad, the Israeli Intelligence service, kidnapped him. He was smuggled back to Israel, accused of crimes against humanity and held until a high profile trial could begin on 10th April 1961 in Jerusalem. (9)

Israeli television broadcast proceedings live, while footage was flown daily direct to the United States. The auditorium was packed with journalists and the building was modified to allow others to watch the trial on closed-circuit television. Newspapers from all over the world published front page stories accompanied by photographs of Eichmann behind bulletproof glass to protect him from assassination. The veracity and volume of media coverage reignited awareness of the atrocities committed in a very recent past. "Too many homes lodge too many ghosts" wrote The Times in London, "the re-telling of their narrative must provoke many of them to reappear." (10) Fulfilling its own prophesy a further 84 articles or major references to Eichmann and his trial appeared in The Times alone between 1st January and 15th December 1961, an average of one every four days for the entire year. (11)

Society was challenged and philosophical debate raged. Was he the man responsible for "the industrialised extermination of a whole race" (12) or as Hannah Arendt wrote after attending the trial as a journalist for The New Yorker, had he been following orders as a thoughtless bureaucrat, and "no deep rooted or radical evil was necessary to make the trains run on time"? (13) Her perspective was that Eichmann was not a monster, but something much worse. A man. It was easy to explain the Nazis as aberrations, but it was much more terrifying to realise that they were human beings, and that all humans were capable of horror. During the trial it was contested that everyone was capable of what Eichmann did, and argued that genocidal tendencies are a facet of human nature.

Sidney, who normally praised the human spirit, explored the lesser nature of man.

"Al Alvarez comes to lunch", he wrote on Sunday 23rd July 1961. Alvarez was a friend and the poetry editor of The Observer. "He is going to Poland. We talk about concentration camps. If we could paint the subject it would be a duty to do so." During the Eichmann trial The Observer had asked Alvarez to write on the camps and Sidney was invited to illustrate the article. He made up his mind two weeks later: "Decide to go to Poland". (14)

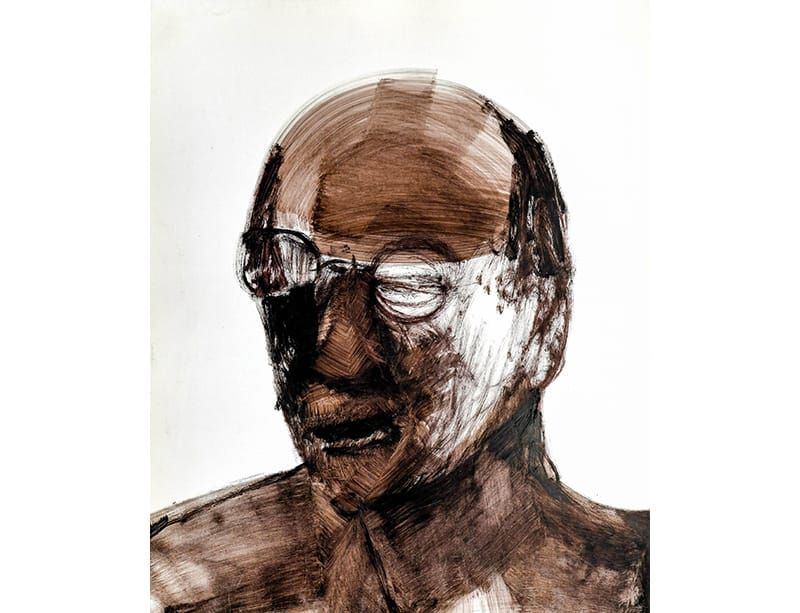

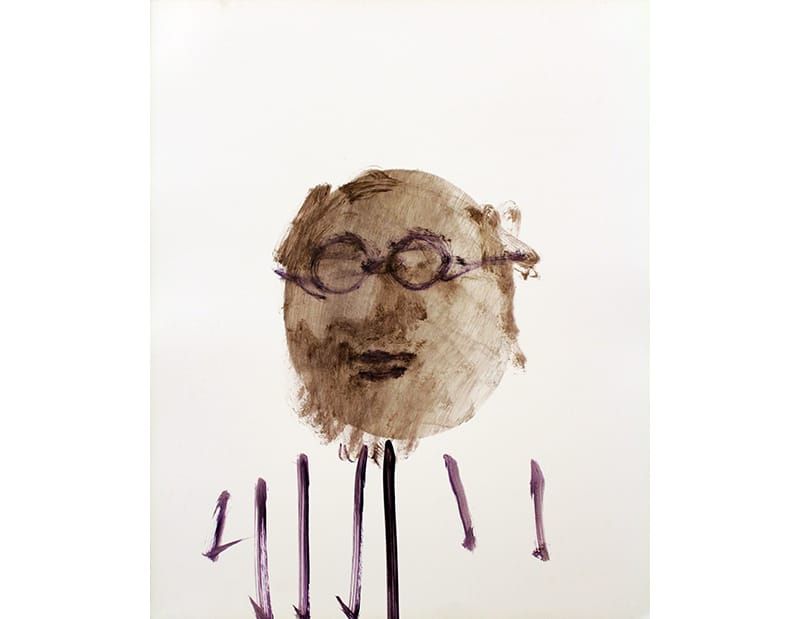

For months the camps haunted Sidney. "Dachau (Winter Snow). Buchenwald / Degas. Maison Tellier" he wrote, "Europe really exists in Poland". (15) Then between 27th November and 10th December 1961, in the two weeks before Eichmann's judges passed sentence, he filled a dozen 63x52cm sheets of paper with the same face and features repeated over and over again. (16) Some in simple outline and others fully formed, every image had the same broad forehead, receding hair, thick rounded glasses, thin lips, and in most a collared shirt buttoned to the top, all mirroring the photographs of Eichmann running almost daily in London newspapers. (17)

Adolf Eichmann, Sidney Nolan, 1961 - Photo by Joe Armao courtesy of Fairfax Media (The Age, Melbourne)

On 12th December 1961 Adolf Eichmann was found guilty of crimes against the Jewish people, crimes against humanity and war crimes. Two days after that, on the 14th December Sidney deliberated, "I am reluctant in a way to dig deeper into Europe but I do not see how the question of the camps can be forever shelved. Perhaps they will never be the material of art, it is impossible to tell. How can a disease be painted?".(18)

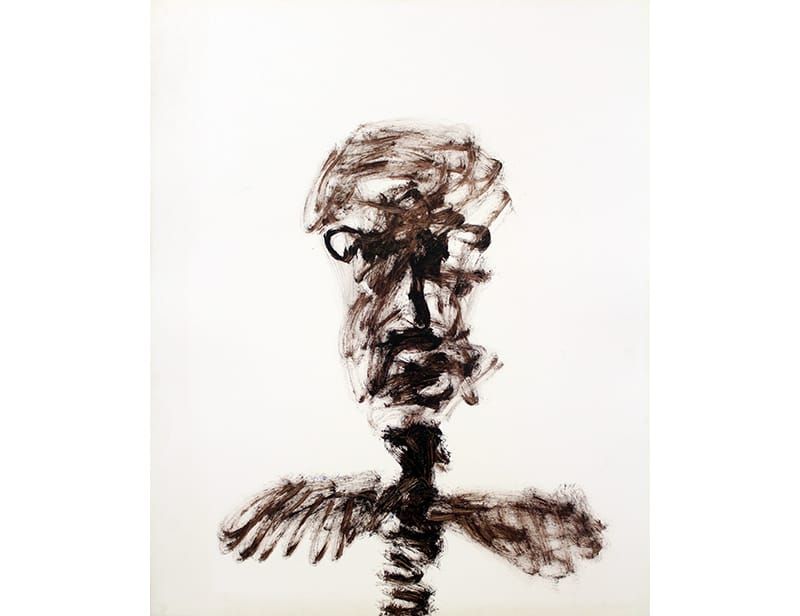

The next day, on 15th December 1961 Eichmann was sentenced to death by hanging and it provided Sidney the release he needed. He immediately switched from the face of Eichmann to over eighty Auschwitz and Concentration Camp heads, kept in a folder under a common title: 'Judges and Victims'. There were three distinct groups of 'Victims' dated roughly six days apart. The first, on the 16th and 18th of December (19), were characterised by prison stripes - faces sliced by bars or vacant eyes above vertical lines on the camp's pyjama-like uniforms. The next dated 23rd December (20) were wreathed in smoke, suddenly clearing to expose harsh heads scratched from paint with screaming mouths. Lastly, dated 29th December (21), there was a group of skeletal heads tortured and twisted. The evolution of images was clear and their titles now unequivocal: ‘Head of Prisoner Concentration Camp’ and ‘Skeletal Head in a German Concentration Camp’. (22)

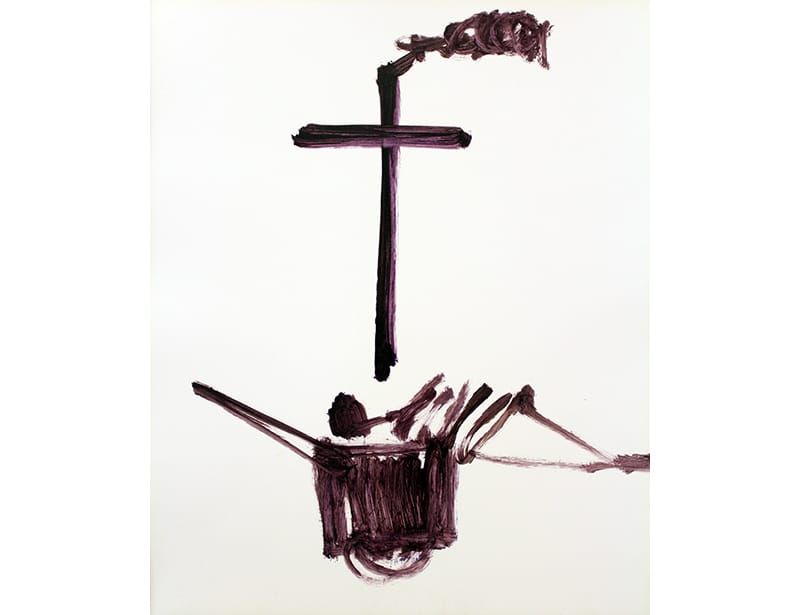

Nine days passed in peace. Then suddenly close to one hundred images poured out, a tortured stream of figures crucified on smoking crosses, skeletons overflowing wheelbarrows and bodies laid out in neat rows of death. At least nineteen of the pictures were dated 7th January 1962 and although all were untitled one was reproduced by Marlborough Graphics in 1967 called 'Camp'. Sidney signed, dated and inscribed 'Auschwitz' on the reverse of the working proof. (23)

The iconography was obvious. Over a million human beings, Jews, Poles and other nationalities, became smoke and ash in the Auschwitz ovens. Faith was death and wheelbarrows were for the living to carry the dead to roll call. With an economy of strokes Sidney's pictures were as convincing as photographs without the slightest hint of enduring myth or "conquering response". There was nothing to redeem the human race.

Sidney travelled to Poland with Alvarez two weeks later on Thursday 25th January 1962 (24) and four days after that, on Monday 29th January, he wrote in his appointment diary with a telling economy of words, "Go to Auschwitz". (25) Alvarez recalled in his autobiography: “The Observer had asked me to write about Auschwitz, and Nolan wanted to illustrate the piece. Auschwitz is a difficult experience to handle, even as a tourist". Facing the reality was not easy, "You grab hold of whatever you can to keep your mental balance". (26)

Standing at the great iron gates under the infamous words "Arbeit Macht Frei" ("Work Sets You Free") the pair could imagine the groans of despair, the screams of guards and Alvarez wrote of the shouted speech that greeted bewildered prisoners stumbling from Eichmann's railway transport:

"You have come here not to a sanitorium but to a German concentration camp from which there is no other way out than through the chimney. If someone doesn't like it he may go out at once through the barb wire; if there are any Jews in this transport, they have no right to live longer than two weeks; if there are any priests, they may live one month, the others - three months". (27)

Prisoners were ripped from their old life, precious possessions torn from their grasp. Stripped naked, they were deloused and beaten, heads shaved bare. Their spirit broken in an instant.

Alvarez went on to describe what Sidney saw inside the gates. "Mountains of human hair, suitcases, spectacles, shaving brushes, artificial limbs. Great mounds of old shoes reach up like rubble after an air raid", (28) all of it covered in dust and human ashes, left as though the owners would momentarily return. In his autobiography he remembered Sidney was "upset less by the obvious horrors – the crematoria, the mountains of shorn hair, discarded spectacles, suitcases and artificial limbs – than by the orderliness of the camps layout". He explained "The interiors of the barracks were dreadful – the tiers of bunks in which the prisoners slept, six men to a bunk, like battery hens waiting to be slaughtered – but the neat grids in which the buildings were arranged troubled him even more". Sidney quietly evoked Kenneth Clark's disdain for abstract art and its lack of humanity. "It looks like a bloody Mondrian" he said. (29)

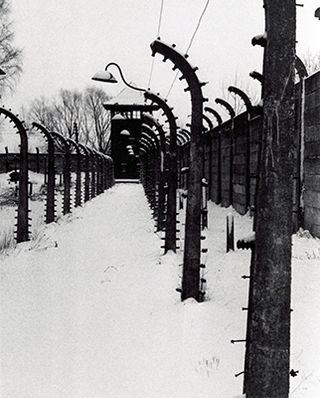

The orderliness of the camp layout, the neat grids in which the buildings were arranged and the industrialisation of slaughter disturbed Sidney the most. Photograph - Sidney Nolan

Overwhelmed by what he saw and felt, Sidney refused to illustrate The Observer article (30). It was an experience for which he had been emotionally unprepared and the trip resulted in an unexpected and lasting retreat from direct Auschwitz imagery. He could not listen to music for months afterwards and more than twenty years later on 6th May 1985 wrote "Am I moving towards Austwitz [sic] painting at last. I hope not". (31)

In the months following the trip Alvarez added to Sidney's turmoil. He sent a draft of his article: "Dear Sid, Here's a draft - much scribbled on. I hope you can make it out. I feel very dissatisfied with it. So do, please, be as ruthless as you can with it. I can't waste this opportunity to get the thing said straight". (32) Sidney kept it in his files, adding his own scribbled thoughts.

Alvarez suggested that in the 20th Century all humanity had the capability to be inhuman. "If they [the camps] were simply the playgrounds for sadists who, in another society would have been locked away, then they were an aberration best forgotten, for they prove that our sickest fantasies can be acted out. The Eichmann affair has shown us that they were not". (33)

He recognised the business of slaughter, writing that the daily amount paid to the camp for the cost of food and depreciation of prisoner's uniforms was balanced against "the profit made from the prisoners personal effects, including dental gold, and the utilisation of his body after death: hair sold to make clothes, fat for soap, bones and ashes for glue and fertiliser". (34) Extermination was a profitable mix of terror and greed, a train of thought that would later follow Sidney to Africa.

Alvarez concluded by echoing Kenneth Clark's belief that the world was abandoning a fundamental humanity. He wrote the camps "can no longer be reduced to the psychopathology of a particular man or even a particular moment in history. Instead they begin to seem like the very psychopathology of everyday life". (35) Although Nazi camps were consigned to history he realised the mentality that created them was not. A mirror had to be thrust into society's face: "We daily handle and are handled by machinery much the same as that which ran the camps; we are daily invited by advertisements and multi-million pound gossip, to gaze in ox-like wonder at the same kind of efficiency.... planes, missiles, computers and even the huge smoothly functioning businesses have an impersonal perfection that is easily mistaken for a high civilisation of their own". (36)

Sidney scrawled on Alvarez's draft, "But high civilisation can perish; and when the civilisation is a world one we cannot afford it.....Art has always been a geiger counter for civilisation". (37)

Six months later

By early September Sidney was in Africa. Shadowy reminders of Auschwitz continued to stalk him across the continent and a deep well of grief was recognisable in many of the African paintings that followed. Nowhere would it be more apparent than in 'Gorilla', a painting privately exhibited to HRH The Queen, and first described by critics as making "savage comment on the futility of the human condition" (38) with "the setting and the object playing strong and clear against each other" (39) then by Sidney himself as possibly "his favourite from the series African Journey”. (40)

On Monday 1st October 1962, in the deep south of Uganda, Sidney prepared to track mountain gorillas. The night before the expedition Walter Baumgartel, famous gorilla protector, conservationist and Sidney's host, explained that he himself had narrowly escaped from Germany before “Hitler got the chance to remove him from life”. (41) The next morning, travelling to the expedition drop off point, Sidney saw local women with shaved heads on all fours working the fields. “The shape of the inevitably shaven heads was very beautiful" wife Cynthia wrote, "but Sidney had visited Auschwitz too recently – an experience which for him, brought the whole of Europe into focus”.

It was in that moment she felt he was beginning to take thematically inventive leaps. "This is the same thing in a way", he had told her, drawing on the concentration camp analogy and referring to the landscape around them. "It's the same closeness to the bone, life pared down to the bone". (42)

Sidney set off with two guides. He trekked Kisoro's cone shaped peaks, misty mountain saddles and bamboo encrusted ravines, hauling himself up slopes slippery from pre-dawn showers, sometimes down on hands and knees fighting through the undergrowth. He saw gorilla nests, footprints and tunnels in the bamboo, while hearing them in the distance barking and crashing through the vegetation. Without a sighting he chased them all the way to the border with war-torn Congo.

He returned in a euphoric state telling Cynthia “it was marvelous, absolutely worth it to me. I’d have gone up every day for days. It’s not necessary to see them, you feel them and you hear them, you crawl and crouch where they’ve gone, seeing the knuckles of their hands where they’ve pressed into the ground feeling their presence everywhere”. (43)

Later, he explained in an interview that while the mountain experience loaded his brush, it was a grainy black and white photograph that compelled him to pull the trigger. “The nearest I got to seeing one was a photograph. Of a dead one. In this guest house affair where the gorilla spotters put up for the night. The photograph is on the wall framed. The gorilla is dead. Rigor mortis has set in and one arm reaches out stiffly. Standing proudly by the corpse is the king of the Belgians, holding a gun big enough to stop an elephant”.

“The gorilla is a kind of man” Sidney said, “He is one of us". Adding "In many ways he’s a better kind of man than we are...He doesn't organise himself into packs. He doesn't make war....So we kill him off”. (44)

On 20th January 1963, with Auschwitz sitting uneasily in recent memory, along with ‘murder’ on the mountain, Sidney pursued ideas on death and the tragedy of man’s lesser nature. Melancholy cloaked him as he reflected on a disappearing world and the human race as a complicit, relentless and insatiable instrument annihilating nature and debasing civilisation. As the painting formed, misty landscapes served as an earthen tomb and the volcanic cones a shrine to “a better kind of man".

Gorilla, Sidney Nolan, 1963

Unlike the Auschwitz works, 'Gorilla' travelled the world - London, Chicago, Australia - but the true nature of the painting was never fully realised. Patrick Hutchins came closest in 1970, sending Sidney a draft speech in which he described the image:

"It is" Hutchins wrote, "as if Chagall had undertaken to make Rembrandt’s flayed ox dance an hasidic ritual". (45)

Andrew Turley

To cite this article use:

Andrew Turley (2020) ‘Nolan’s Auschwitz’ (an extract from ’Nolan’s Africa’), published by the Sidney Nolan Trust on the exhibition of 'Sidney Nolan: Colour of the Sky - Auschwitz Paintings' held at The Rodd, Presteigne, United Kingdom, opened 13 August 2021.

REFERENCES

- Sidney painted 'Paradise lost', gouache on newsprint unsigned but dated 1939 and between the fold inscribed "Paradise lost, paradise regained, the divine comedy [ileg] pit, concentration camp", 30.5 x 36 cm, private collection. In the same year he painted 'Prison Camp', gouache on newsprint overpainting a photograph of inmates at Buchenwald concentration camp wearing black and white stripe uniforms from the Argus Weekend Magazine, 28th October 1939 with "Camp / Elisabeth / Tears (St Kilda Beach)" inscribed on the back, 23.5 x 18.5 cm seen in 'Sidney Nolan Across Continents exhibition catalogue, 8th September - 8th Oct 2010, Agnew's Gallery, London, 2010. 'Lublin' or 'Baroque Exterior' was painted in 1944, synthetic polymer paint on composition board, 61.7 x 92.0cm, gifted by Sidney and Cynthia Nolan in 1974 to the Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide. In 1947 he also completed a transfer drawing of a body in a brick kiln with a large head floating in the smoke above a chimneystack. It was also titled 'Lublin', initialed on the reverse "13-1-47, Lublin", 25 x 31.5 cm in a private collection

- Confirmed in discussions on 16th Dec 2019 with Emeritus Professor Konrad Kwiet historian and scholar of the Holocaust, Pratt Foundation Professor at the University of Sydney and Resident Historian at the Sydney Jewish Museum governing the historical accuracy and authenticity of the exhibition content. Having worked in universities, museums and research centres in Heidelberg, Israel, Washington DC, Oxford and Berlin, he was appointed as Chief Historian at the Australian War Crimes Commission (SIU) in the mid-1980s, has read and listened to more than 1,000 testimonies of Holocaust survivors, and has concurrently published 10 books and more than 100 articles

- George Ivan Smith remarks at Sidney Nolan's Memorial Service, 22nd April 1993, Tate Archive 2019 p.1-2

- 'Alleged Bargain with Nazis over Hungarian Jews', newspaper article hand annotated by Sidney Nolan in blue ink "The Times 24th June 1955" in The Papers of Sidney Nolan, MS10245, National Library of Australia

- 'Head in profile' (1957), mixed media on paper, 30.5 x 25.4cm, dated "7/8/57" and inscribed "Do European Scene of Camps on scale of Lascaux" on the reverse, in a private collection

- Katie Cranford, 'The Trial of Adolf Eichmann in Israel', Memorial University of Newfoundland in Mapping Politics Vol 8 No.3 Changing Political Landscapes Conference Preceedings, Memorial University 2017 p.108

- Ibid p.109

- Sydney Jewish Museum confirmed in discussions on 16th Dec 2019 with Emeritus Professor Konrad Kwiet historian and scholar of the Holocaust

- Katie Cranford, 'The Trial of Adolf Eichmann in Israel', 2017, p.110

- 'Disquiet in Israel over Eichmann trial', The Times, London Thursday 6th April 1961 p.9

- The Times archive of content published 1st January 1961 to 15th December 1961 referencing 'Adolf Eichmann' accessed 2018

- Zvi Aharoni and Wilhelm Dietl, 'Eichmann Operation: The truth about the pursuit, capture and trial', John Wiley and Sons New York, 1997

- Hannah Arendt, 'Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil', New York, Viking Press New York 1963

- Sidney Nolan 1961 Commercial Diary entries on Sunday 23rd July 1961 and Sunday 6th August 1961 in The Papers of Sidney Nolan, MS10245, National Library of Australia

- Ibid. Friday 3rd November 1961

- A large sequence of works from a folder titled 'Judges and Victims' in Sidney Nolan's handwriting from a private collection. Two Eichmann works in the sequence were dated on the reverse - "27 Nov 61" (also inscribed "Judges and Victims") and "10th Dec 61".

- Eichmann photographs appeared three times in the Daily Mirror alone during the short window Sidney was painting - on Wednesday 22nd November 1961 p.12, then 28th November 1961 p.18 and Friday 8th December 1961 p.8.

- Sidney Nolan 1961 Commercial Diary, Thursday 14th December in The Papers of Sidney Nolan, MS10245.

- Dated works from this group include ‘Auschwitz figure behind bars', 1961, mixed media on paper, 52 x 63.5cm. Signed and dated "16.12.61" lower centre left; signed, dated and with JF19/34 on the reverse. As well as three versions of ‘Auschwitz figure in striped uniform’, 1961, mixed media on paper 63.5 x 52cm, all signed and dated "18-12-61" lower left and consecutively marked JF19/38, JF19/40 and JF19/42 on reverse, from private collections.

- Three works of the same style all titled 'Head of Prisoner in German concentration camp' and all dated 23rd December 1961 can be found in the collections of the Australian War Memorial with accession numbers ART91376, ART91377 and ART91379. Additionally another nine works of similar style all signed and dated 23rd December 1961 with various titles 'Auschwitz figure in striped uniform', 'Man Auschwitz' and 'Auschwitz figure' are in private collections.

- Six works of the same style titled 'Skeletal head 3’, 'Skeletal head 5’, 'Skeletal head in German concentration camp’, 'Head of German prisoner in concentration camp’, 'Skeletal head’ and ‘Head’ and all dated 29th December 1961 can be found in the collections of the Australian War Memorial with accession numbers ART91368, ART91369, ART91370, ART91371, ART91372 and ART91375.

- Australian War Memorial accession number ART91387 'Head of prisoner in German concentration camp' and Australian War Memorial Accession number ART91369 "Skeletal Head in a German Concentration Camp".

- Camp 1966-67 screenprint - a working proof, 70.8 x 49.7cm dated 25th Jan 1967, printed by Kelpra Studio London and published by Marlborough Graphics, in a private collection.

- Sidney Nolan 1962 Appointment Diary from 25th January 1962 "Arrive Warsaw Grand Hotel" in The Papers of Sidney Nolan, MS10245 National Library of Australia.

- Ibid Monday 29th Jan 1962 "Go to Auschwitz"

- Al Alvarez, 'Where did it all go right?', Bloomsbury, London 2002 p.270

- Al Alvarez, 'The Concentration Camps', 1962, p.5

- Ibid p.1. The full paragraph reads: "Yet despite the mementos of death, the process is abstract and anonymous....Perhaps this is as well, since the reverse is a psychopathic, chamber-of-horrors view, which fixes on the details of pain and torture to the exclusion of everything else, it has made descriptions of Nazi atrocities best-sellers in the shady bookshops of Soho. It also makes the camps unimportant: if they were simply the playgrounds for sadists who, in another society, would have been locked away, then they are an aberration best forgotten; for they prove only that our sickest fantasies can be acted out. The Eichmann affair has shown that they were not"

- Al Alvarez 'Where did it all go right?', 2002, p.270

- Sidney Nolan 1961 Commercial Diary Thursday 14th December in The Papers of Sidney Nolan, MS10245. Sidney recorded his misgivings about trying to paint Auschwitz, writing "Met Al Alvarez in town for lunch. Discuss trip to Poland to see Concentration Camps....Al and I to go for a week in January. Whether I will do paintings?"....Perhaps they will never be the material of art, it is impossible to tell". However it was not until visiting the Camp that he made his decision. Before travelling, on Thursday 4th January 1962 in his 1962 Appointment Diary, he wrote "Go to "Observer" Michael Davie visit Poland (28th Jan) material due last week March for Easter. 2 front magazine pages + 1 follow up inside"

- Nancy Underhill, 'Nolan on Nolan', 2007, p.56 referencing Sidney Nolan Diary note from 6th May 1985

- Al Alvarez sent 'The Concentration Camps' nine page draft to Sidney Nolan with a hand written cover letter on The Observer letterhead. Sidney retained the complete correspondence in his personal files with his own hand written notes.

- Ibid p.1

- Ibid p.7

- Ibid p.8

- Ibid p.9

- Ibid Sidney Nolan hand written notes on the reverse of Al Alvarez's cover letter

- Anthony Retallack, 'Sidney Nolan', The Arts Review, Vol XV No.8, 4-18 May 1963, p.7

- Nigel Gosling, 'Sidney Nolan on Safari', The Observer, 12th May 1963, p.28

- Larry Boys, 'Africa in Vivid Nolancolour, Roving Reporter of Art: Larry Boys in London', The Bulletin, Sydney, 24th August 1963, p.32

- Cynthia Nolan, 'One Traveller's Africa', Methuen and Co Ltd London, 1965, p.138

- Ibid p.142

- Ibid p.150

- Larry Boys, 'Africa in Vivid Nolancolour', 1963, p.32

- Patrick Hutchins introductory notes titled 'Nolan 40-70' including hand written edits by Sidney Nolan - dated and inscribed PH 23/xii/70, Patrick Hutchins University of WA, p.5 The Papers of Sidney Nolan, MS10245 National Library of Australia.